Understanding Sticky-Shed Syndrome -

Description, Treatment, and Tape List

This article explores a phenomenon known as “Sticky Shed Syndrome” (SSS), which primarily affects magnetic tapes from the 1970s and 1980s. It presents methods for treating tapes in preparation for digitization and offers a brief overview of Wendy Carlos (why not?), a pioneer of electronic music. You will also find a list of affected tapes and models, along with some valuable additional notes.

To jump directly to the section describing the SSS treatment and the list of affected tapes, click here.

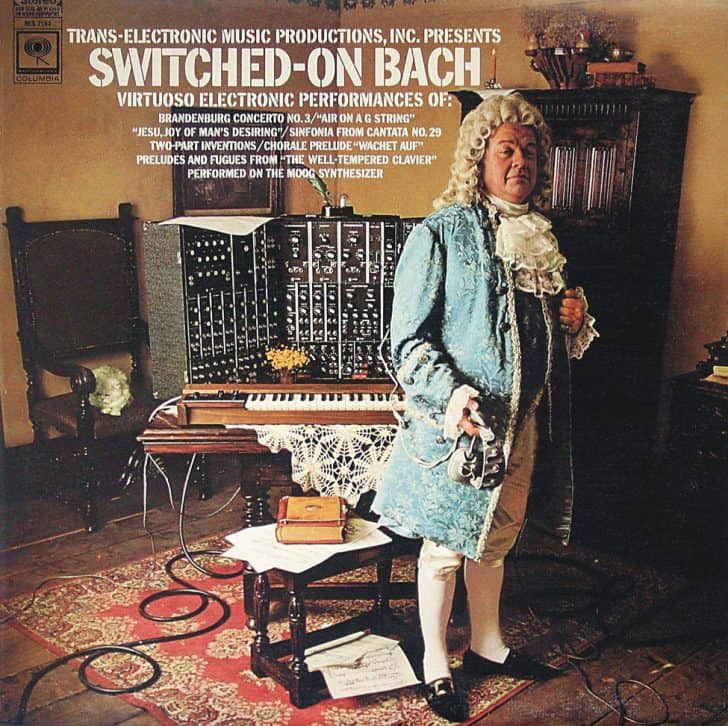

Wendy Carlos, born in 1939 in Pawtucket, Rhode Island (Family Guy fans might recognize the name?), is a pioneer of electroacoustic music. In the late 1960s, she recorded several classical works by Johann Sebastian Bach and other Baroque composers using the famous Moog modular synthesizer. Wendy Carlos actively contributed to the development of the Moog synthesizer through her collaboration with Robert Moog, whom she met in 1968.

Her groundbreaking album Switched-On Bach (1968), initially recorded on a custom 1″ 8-track tape recorder (Ampex 300/351), marked the first time synthesizer sounds were introduced to the public in a non-experimental context. This album is a milestone in electronic music production, and if you ever get the chance, it’s definitely worth a listen.

Wendy Carlos is not only an accomplished musician, having developed her own musical scale, but also a prolific composer, responsible for the soundtracks of films such as A Clockwork Orange and Tron. Like many musicians of the ’70s and ’80s, her music was originally recorded on master audio tapes from that era. And that’s when she decided to transfer her master tapes to digital. And, well, you can probably guess where this is going…

Returning to these old tapes and placing them on a reel-to-reel player after all these years can have serious consequences if you’re not careful. Some of the most popular tapes from the 1970s, 1980s, and even into the 1990s may suffer from a condition known as Sticky Shed Syndrome (SSS) for short.

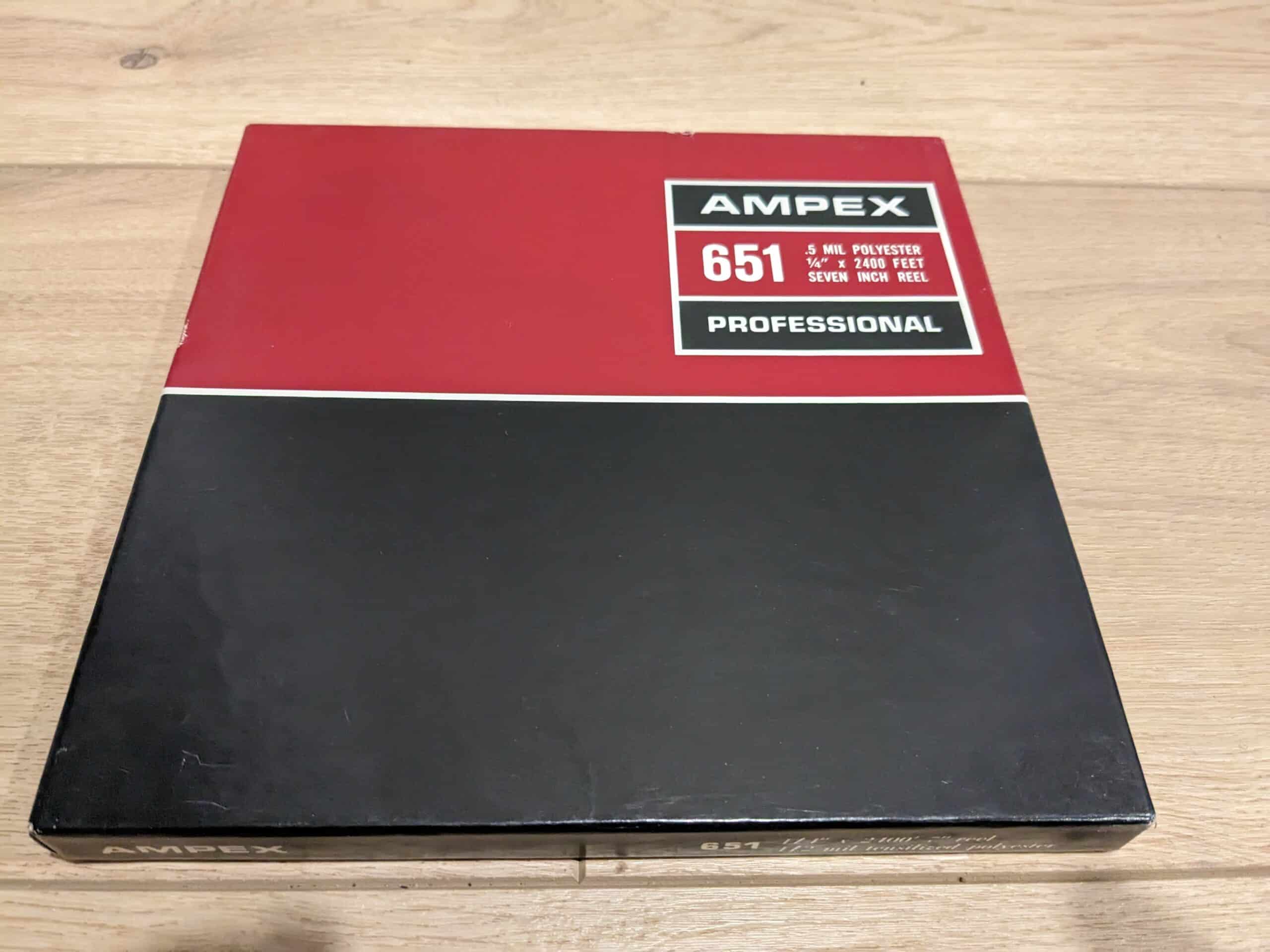

It is essential to note that only polyester tapes are affected, and generally, those with a black back coating are the most at risk. If you own tapes from the 1960s or earlier, they are likely made of acetate and do not suffer from Sticky Shed Syndrome (SSS). To distinguish them, hold the tape up to your eyes with a light source behind it. If the light passes through and the tape appears translucent, it is acetate. Do not bake acetate tapes.

If the tapes are opaque, they are most likely made of polyester, and you can also check the box if you still have it.

If your tapes suffer from Sticky Shed Syndrome and you decide to play them on your reel-to-reel tape machine, here’s the issue: as the tape passes over the guides and heads of the machine, the adhesive that holds the ferromagnetic particles to the plastic tape tends to stick to the non-rotating components in the tape path (guides, heads). This causes these particles to deposit onto the stationary parts. These particles are crucial for preserving the magnetic information, and in this case, the recording. Unfortunately, this scenario is not only problematic but also irreversible.

The extent of the damage caused by Sticky Shed Syndrome depends on how severely your tape is affected. In mild cases, it may result in a small brownish deposit on the tape path, leading to a permanent loss of high-frequency content in the recording. In severe cases of SSS, a significant buildup occurs on stationary components, resulting in the loss of much more than just high frequencies.

As a side note, I once purchased a tape recorder from someone who believed their machine was faulty due to poor, muffled sound quality. It turned out that they had played a tape affected by Sticky Shed Syndrome on the device. As a result, not only was the tape problematic, but the heads were also coated with tape residue. Even a good tape would not play correctly in that condition. Fortunately, all that was needed was a thorough cleaning of the heads using a cotton swab and isopropyl alcohol.

When it comes to tapes, fortunately, there is a simple solution—even Wendy Carlos used it. The trick is to bake them. It was discovered that removing the absorbed moisture from the binder (the adhesive) can temporarily fix the problem, providing enough time to transfer the tape to digital or onto a new tape. For 1/4-inch reels, a stable low temperature between 130-140°F (about 54-60°C) for approximately 4 to 6 hours is sufficient, while 2-inch reels may require up to 12 hours. It is important not to use your oven; instead, use a food dehydrator, which you can find on Amazon—it’s ideal for this type of task.

If your tape is listed in the list below, it is recommended to “bake” it. If it is not on the list, you can still bake it as a precaution; it won’t harm the tape as long as it is not acetate.

Remember: do not bake acetate tapes.

Otherwise, you can perform a test on your reel-to-reel player by using a small portion of the tape. Play it for a few seconds, stop the tape, do not rewind—simply remove it from the path and check for any residue. If there is no residue, you can proceed with playing the entire tape and perhaps check again after a few minutes to confirm.

The same test method applies to a tape affected by SSS. After the baking process, perform a test, and if it still leaves residue, consider baking it for a few more hours. Once the process is complete, rewind the tape while bypassing the stationary parts of the path if possible.

Don’t forget to also clean and demagnetize the parts that come into contact with the magnetic tape on your tape player, such as the playback heads and guides.

As a final note, although audio tapes and SSS are commonly discussed, it’s important to mention that some video cassettes can also be affected. For example, open 1/2-inch video reels for the Sony EIAJ-1 video format from the 1970s may require “baking.”

This method can also be effective in resolving squeaking issues with 3/4-inch U-Matic video cassettes inside the player, except for those leaving a dry white residue (see the note below).

Sticky-Shed Syndrome

Treatment and Affected Tapes

To summarize the information above, to treat polyester tapes affected by SSS, place them in a dehydrator at a temperature between 130 and 140 °F (54-60 °C) for 4 to 6 hours. This should be sufficient for 1/4-inch tapes. Wider formats will require more time in the dehydrator, up to 12 hours.

You can also contact us for professional treatment and digitization of your tapes.

List of Classic Tape Stocks Affected by Sticky Shed Syndrome

Ampex/Quantegy

– 406/407, 456/457, 478, 499, 2020/373, 3600, 196 (1-inch video), 197 (3/4-inch video)

Scotch/3M

– 211, 226/227, 250, 806/807/808/809, “Classic” and “Master, Master-XS” 908, 966/986, 967, and 996 (50% of the time)

Sony

– SLH, ULH, FeCr, PR-150

Based on our experience, Sony KCA Series (KCA-20, KCA-30, KCA-60) U-Matic 3/4-inch video cassettes can exhibit a unique issue, leaving a dry white residue. This is not mold but rather lubricant deterioration. Unlike Sticky Shed Syndrome, this problem does not seem to be resolved by baking. Instead, it appears to be mitigated by playing the cassette multiple times until it stabilizes. During this process, it is recommended to clean the tape path and heads between plays for optimal results.

Agfa

– PEM 469, PEM 369

Tapes Showing Mild Deterioration

In most cases, treatment consists of running the tape through a cloth at high speed.

Scotch/3M

– 201 (Acetate)

– 206/207

Article written by Patric Favreau: Understanding Sticky-Shed Syndrome – Description, Treatment, and Tape List